A MYSTERY over a carved Roman stone that has puzzled experts for decades may have finally been solved – by artificial intelligence.

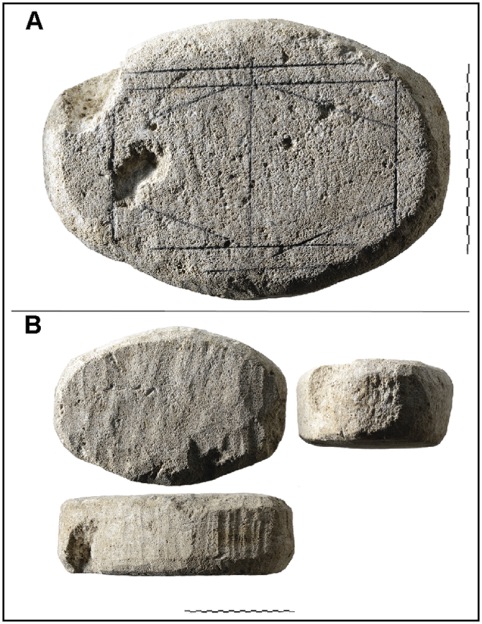

The rounded hunk of limestone has a strange pattern carved into the top that dates back thousands of years.

The mysterious Object 04433 from Het Romeins Museum has carved lines that may have been used for ancient gamingCredit: Antiquity / Cambridge University Press / Walter Crist

The mysterious Object 04433 from Het Romeins Museum has carved lines that may have been used for ancient gamingCredit: Antiquity / Cambridge University Press / Walter Crist

Limestone was commonly used for building at the Roman town of CoriovallumCredit: Antiquity / Cambridge University Press / Het Romeins Museum

Limestone was commonly used for building at the Roman town of CoriovallumCredit: Antiquity / Cambridge University Press / Het Romeins Museum

Archaeologists suggested that it could be a board game as far back as 1984, but no one was quite sure.

Now experts have used a combination of 3D imaging and to reveal that not only was it likely a board game, but the exact rules that the Romans might have used to play.

“The object bears an incised geometric pattern on its top surface that has not previously been identified on other artefacts,” said lead author Walter Crist, of Leiden University.

The object is named 04433 and is currently stored at the Het Romeins Museum in the .

It’s a worked piece of white Jurassic limestone weighing just over three kilos, and is sourced from the quarries at Norroy in north-eastern , the researchers say.

The limestone was often used at Coriovallum, where the stone was found.

Coriovallum was a town in the province of Germania Inferior.

It was founded under the reign of (the ), who reigned from 27 BC to 14 AD.

But the town itself was inhabited until the Western Roman Empire fell in 476 AD.

The remains of the town now lie beneath the present-day Heerlen, which is in the Netherlands.

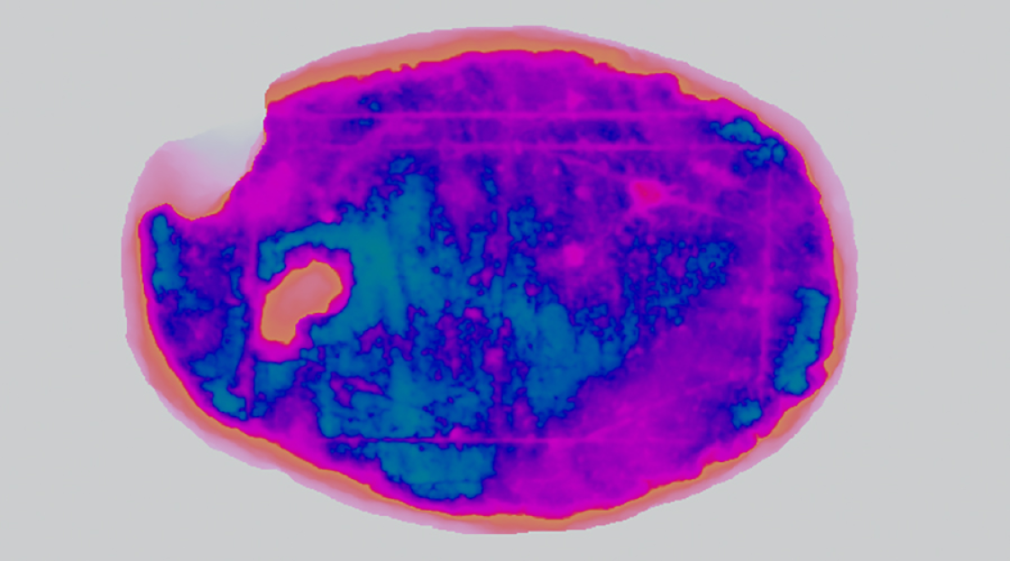

This depth-map visualisation shows low surfaces in pink along the lines of the object, and is ‘notably smooth’ along the bottom-right diagonalCredit: Antiquity / Cambridge University Press / Walter Crist

This depth-map visualisation shows low surfaces in pink along the lines of the object, and is ‘notably smooth’ along the bottom-right diagonalCredit: Antiquity / Cambridge University Press / Walter Crist

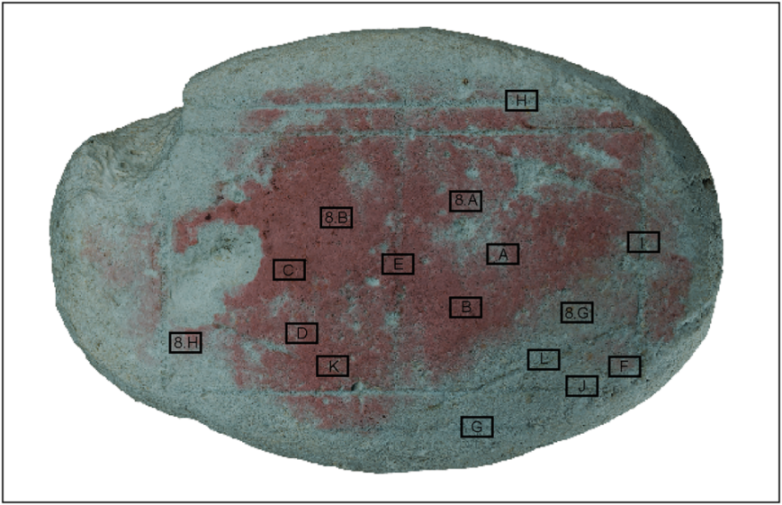

This is the depth map superimposed on a real-colour image of the stoneCredit: Antiquity / Cambridge University Press / Walter Crist

This is the depth map superimposed on a real-colour image of the stoneCredit: Antiquity / Cambridge University Press / Walter Crist

And after probing the stone using 3D imaging, experts were able to reveal that some lines were deeper than others, hinting at pieces being moved along them.

“Lines incised on a piece of rounded limestone found at the Roman site of Coriovallum in Heerlen, The Netherlands, evoke a board game yet do not reflect the grid of any game known today,” Crist said.

“We conclude that the object was most likely used as a game board, though other interpretations cannot be entirely ruled out.”

He added: “Disproportionate wear along specific lines favours the rules of blocking games, potentially extending the time depth and regional use of this game type.”

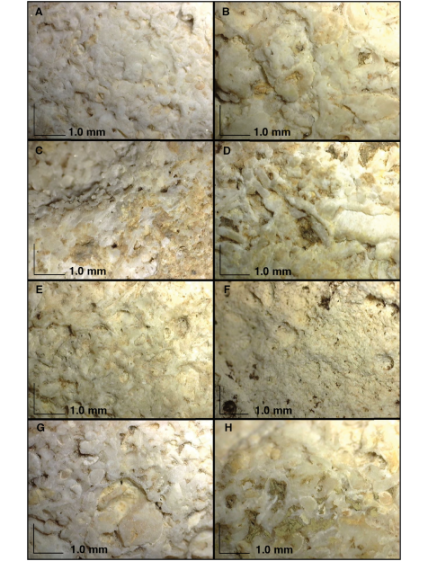

These close-ups show a mixture of smooth and ‘abraded’ parts of the stoneCredit: Antiquity / Cambridge University Press / Walter Crist

These close-ups show a mixture of smooth and ‘abraded’ parts of the stoneCredit: Antiquity / Cambridge University Press / Walter Crist

Importantly, they noted that the grinding of foodstuffs, pigments, or other materials wouldn’t have produced this pattern.

Instead, scientists say that the use-wear on the stone was “plausibly created through gameplay”.

“The fact that the observed wear pattern is only apparent in parallel with the incised lines suggests that those lines were meaningful for the action that produced abraded wear along them,” the study authors explained.

They used AI to model what sort of games might have been played on the stone.

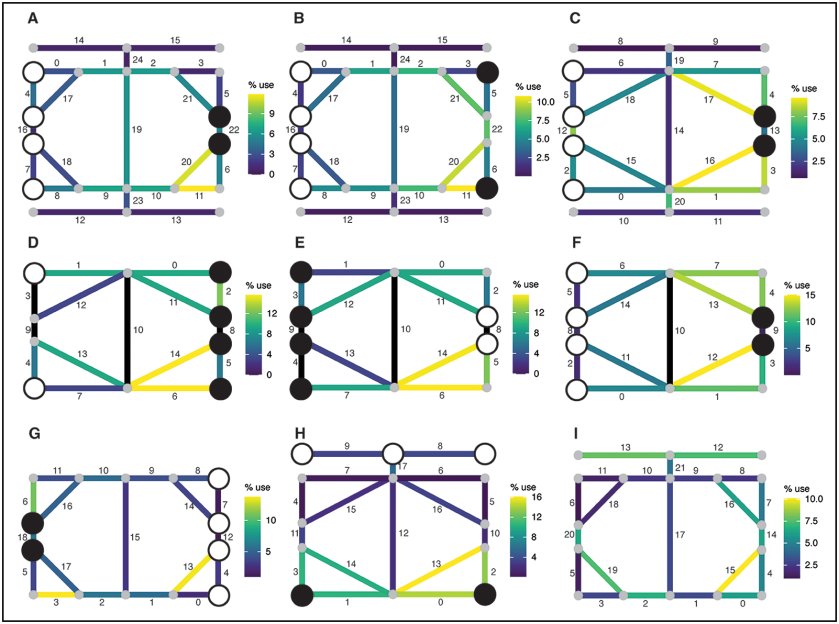

These are the results of the AI-driven simulation that produced ‘asymmetrical play’ along the relevant diagonal line highlighted on the depth mapCredit: Antiquity / Cambridge University Press / Walter Crist

These are the results of the AI-driven simulation that produced ‘asymmetrical play’ along the relevant diagonal line highlighted on the depth mapCredit: Antiquity / Cambridge University Press / Walter Crist

And that simulations involving a “blocking game” most frequently matched the wear-patterns seen on the stone.

Specifically, the game would’ve seen one player starting with four pieces on one vertical side of the main rectangle.

And they would’ve had to block their opponent’s two pieces, which would’ve started on the opposite side.

The experts say this is the most likely “playable game” that could explain the pattern seen on the stone.

The town of Ciriovallum is beneath modern-day Heerlen in the NetherlandsCredit: Antiquity / Cambridge University Press / Walter Crist

The town of Ciriovallum is beneath modern-day Heerlen in the NetherlandsCredit: Antiquity / Cambridge University Press / Walter Crist

And it was found at a busy Roman hub, where it’s entirely possible that people were playing this kind of game.

The town of Ciriovallum, where the stone was found, was in a strategic spot, the experts say.

It was connected to two main arteries of the ancient Roman road system.

And in particular, it became an important centre for the production of Roman-style pottery.

These glass game pieces – also stored at Het Romeins Museum – have been found at Coriovallum

These glass game pieces – also stored at Het Romeins Museum – have been found at Coriovallum

The archaeologists say that at its peak, Coriovallum would’ve covered just over 48 hectares, with burial grounds that stretched out for nearly a kilometre along the four main roads out of town.

“The ability to identify play and games in archaeology strengthens the understanding of our ludic heritage,” the study authors said.

“And makes ancient life more accessible to people in the present, as the act of playing a board game is fundamentally the same today as it was in past millennia.”

This research was published in the journal Antiquity and published online in partnership with the Cambridge University Press.